Information Gain and College Football

Examples of how college football flexible scheduling can generate more information for playoff seeding.

As we look at the college football playoffs every year, we’re collectively asking ourselves: what do we know about the elite teams? And the answer, resoundingly, is “not very much.”

College Football is a sport divided into haves and have nots. Every year, there are a handful of juggernaut teams, and a handful of also rans. This year, it looks like Oregon, Texas, Ohio State, and Georgia are the juggernauts—and everyone else is along for the ride.

But we don’t really know. Because apart from two games—Georgia versus Texas and Ohio State versus Oregon—most of the games these teams have played have not given us very much information about the teams.

When we think about team strength, it is helpful to use a metric like Elo rating, which abstracts everything about the team into a single number. These numbers are not perfectly accurate, but they have proven to be consistently effective across almost all paired competitions.

Elo ratings work by providing an estimate of teams strength, based on past performance, and then updating that estimate when teams play new games. The update amount is based on the probability of winning—which is, in turn, derived from the relative difference in estimated team strengths.

This updating method is also a convenient measure of information gain. A bigger update—up or down—means that we learned more information about the team.

When teams play teams of equal estimation—for example, when Georgia and Texas play—there is a high probability of a medium sized update.

When teams play teams of widely varying estimation—for example, when Ohio State plays Akron—there is a small chance of a big update, and a big chance of nearly no update.

To look at an example of the problems this causes, we can look at Ohio State’s schedule this year.

In all but two of Ohio State’s game, we expect to learn next-to-nothing about Ohio State. In more than 80% of the games, Ohio State has an 85% chance of winning.

The only two games we expect to learn something are their marquee matchups against Oregon and Penn State.

But because they play so few games relative to their very strong peers, we get next-to-no evidence to differentiate them from these peers.

In fact, in our example, Ohio State’s rating only moved 2 points over the entire season—even considering their “surprising” loss to Michigan. Surprising is in scare quotes there, because a loss to a Michigan-strength team was expected, given that Ohio State is a very strong team and they played the schedule composed the way it was. Ohio State’s expected record was 10-2 — and we expected them to beat either Oregon or Penn State, and lose one other game.

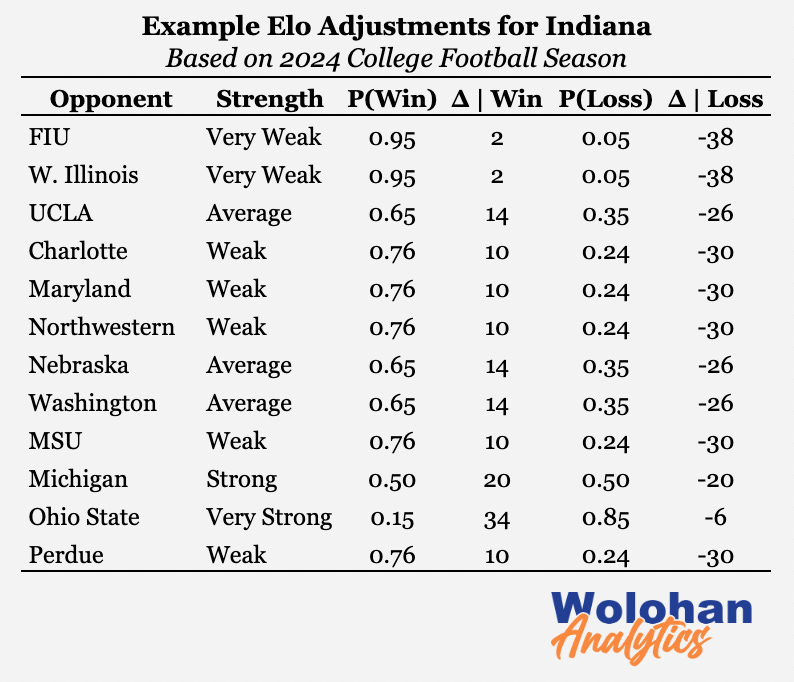

Let’s play this out with Indiana to see how this works for a borderline playoff team.

Indiana had a great season. They were expected to win 9 games and they won 11. The only game they lost was a game they had only a 15% chance of winning. They won their coin-toss game against Michigan and dominated a bunch of weak to very weak opponents.

But what did we really learn?

That IU is competitive against Michigan-level teams? Indiana is projected to play Texas or Georgia in the opening round, against whom they’ll be given about a 15% chance of winning. That may be generous.

If the goal of the season is to differentiate which teams are worthy of being in a 12- , soon to be 14-, team playoff—did we really accomplish that if we cannot differentiate Indiana from Michigan?

Last week, we proposed a flexible-scheduling approach, where teams could be flexibly scheduled against opponents where we could learn relatively more information than under the current system. What might that look like?

Big Ten teams play 9 conference games each year. So let’s assume the first four of those are fixed-schedule games, the last four are flexible scheduling games, and the final game is a fixed-rivalry game (e.g., OSU-Michigan, IU-Perdue, Minnesota-Wisconsin, etc.)

Under our recommended approach, IU would swap its games against weaker teams Washington and Michigan State for strong teams: Illinois and Iowa. IU would have a lower chance of winning these games—they would be near coin-flips—but we would learn much more about IU as a result. This would guarantee that if IU goes 11-1, it is not because they only played one meaningful game all season.

Under this scenario, the frequency that we learn something about teams is significantly increased. As is the amount we learn about teams that we expected to win.

But can you really do flexible scheduling? Won’t that create a logistics nightmare and make it hard for fans to buy tickets? No. Fans already do this for playoff games. Any playoff is effectively a flexibly scheduled event, and playoff games have excellent attendance.

Further, these games are de-risked by season ticket packages and student tickets. And the television dollars that will be brought in for these more competitive matchups will be bigger than for less competitive matchups.

The conferences might use a combination of the following criteria to set flexible scheduling:

Wins

Computerized Rankings, e.g., Elo- or BCS-style rankings

Media / Coaches Poll Rankings

Television Interest

What keeps a conference from giving their top teams the easiest path to the championship?

Nothing. But if we look at schools like Oregon, who played only one of the top three schools in their conference, there is a good argument that conferences are being lenient on their best teams now.

Similarly, Texas played Georgia (and lost big), while also dodging CFP-eligible teams like Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Ole Miss. Texas should have played better competition down the stretch so we know who they are.

Ultimately, the way we schedule games is leaving too much on the table. And if we want to take the playoff seriously, we need better information heading into the playoff. Right now, we simply don’t have meaningful evidence about the quality of the strongest teams.