The Regular Season Should Matter

But what does that really mean?

College football has a problem. The season is over and the playoff committee has picked some truly undeserving teams: even by their own estimation.

But what’s worse: they left out one of the best teams in the country.

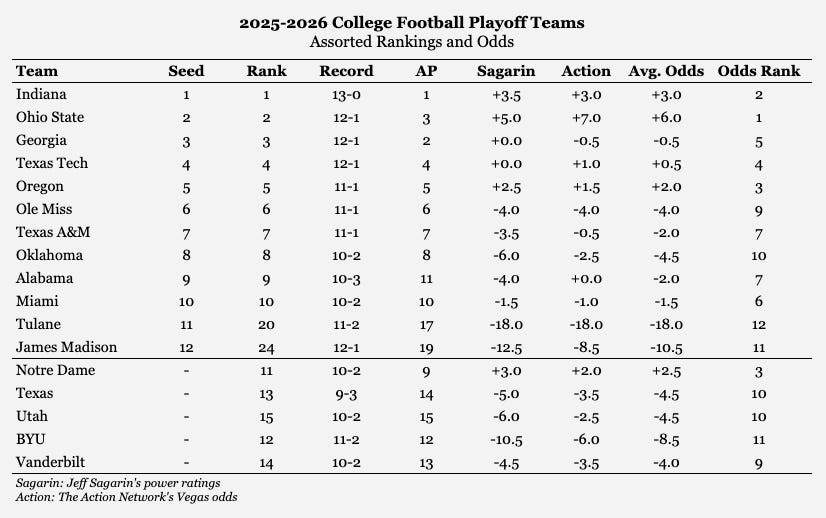

By their own admission, the Playoff Committee left out Notre Dame and BYU, who they had as the 11th and 12th best teams in the country, in favor of the 20th and 24th ranked Tulane and JMU.

What is startling about this, is that the committee seems to be living in their own world.

The Associated Press had Notre Dame ranked 9th, ahead of final two at large teams – Miami and Alabama – and Vegas had Notre Dame as -2 to -4.5 point favorites over those teams. In fact, Vegas had Notre Dame as the third best team in the field: good enough for the second at large spot, after Ohio State.

The rules for the playoff are as follows: the five highest-ranking conference champions (Indiana, Georgia, Texas Tech, Tulane, and James Madison) get automatically admitted, along with seven at-large teams.

The goal, purportedly, is to make the regular season matter. But there’s a problem. People differ greatly on how they view what the regular season mattering means.

The traditional view: just win the games in front of you.

The traditional view is that a team has no control over its own destiny and that it can only play the teams on its schedule. From there, if it wins those games, they should be rewarded.

If you beat another team, that should count as a tiebreaker, if the records are even.

If we use this model: Alabama should be out. After all, there are simply too many undefeated, 1, and 2 loss teams to let in.

This naive approach has its problems, but it is fair. If you win, you can get in.

There are two obvious retorts.

Not every team plays similarly hard schedules. Power Four teams, especially, play harder schedules than Group of Five teams.

Not all losses are created equal.

The desire to include a Group of Five team is an odd one. College Football is hoping for an underdog story that never comes – or even seems likely. But this could still be easily addressed. Just penalize Group of Five teams whenever there is a tie, unless their losses come from Power Four schools.

James Madison’s one loss came to a respectable Louisville team that also beat Miami. It seems fair enough to treat them as a standard one loss team.

Tulane, however, has a loss to Group of Five UTSA. In that case, it seems fair enough to give preference to the teams that lost the same number of games, but against tougher competition.

If we applied that simple rule, we’d have 8-teams in, and we’d need to select four more teams from the following list: Notre Dame, Miami, Vandy, OU, Utah, and BYU.

Alabama and Tulane lose out.

The Season as a Giant Playoff

Another common, traditional view is to think of the season as a giant playoff. In this way, we’re still punishing teams for wins and losses, but we’re also thinking about it as a sort of feeder-system into the playoff.

The teams are not floating, free form. They’re aligned to conferences – like the National Football League has divisions or the World Cup has pools – and those conferences get slots in the playoff.

In effect, you’re in a giant tournament the whole season.

College Football wants to do something like this. That’s where their idea of the top-five highest ranking conference champions comes from.

The flaw comes from how each of the conferences determines its champion.

Conferences are deep. And just like we have a problem with determining who should be in the College Football Playoff, conferences have the same problem determining who should play in their championship game.

The ACC matched Virginia against Duke – but had several other two-loss options including: Miami, Pittsburgh, SMU, and Georgia Tech. All four of those teams were rated higher than Duke by Vegas, but because of the ACC’s selection criteria, Duke got the nod and upset Virginia in the championship.

Unfortunately, because of their poor performance outside the conference – they were ineligible for post-season play. Invalidating the idea that the season is a giant tournament.

You have some conferences – like the Power Four ACC – who simply do not subscribe to this model.

The other indication that College Football doesn’t take this idea seriously is that it doesn’t have automatic bids. If the champions matter, Duke should be in. After all, it won a Power Four conference.

Vegas would favor them over Tulane on a neutral site. Even somehow that is less offensive.

The Bayesian View

Another way to view seasons – especially popular among stats nerds and gamblers – is to view every game as a chance to update your rating about a team. Statisticians take a strict view about this. Every team gets a rating and then gets rewarded or penalized for their wins and losses. But it has also bled a bit into popular analysis.

This makes analysis of losses and head-to-head tricky, because the strict-statistical view is opposite the conventional wisdom here.

In the conventional view, if Miami and Notre Dame finish 10-2, and Miami beats Notre Dame during the season, Miami should get the nod over Notre Dame. Miami beat Notre Dame head to head, so we should reward them for winning that game.

Statistically, however, because Miami’s loss comes to a team worse than themselves, we would actually want to punish Miami more for losing to that team. In the statistical view, Notre Dame didn’t lose to “Miami”, they lost to a team with a Miami-like strength. Miami, on the other hand, lost to a team with worse than Miami-strength. So Notre Dame gets the nod in this case.

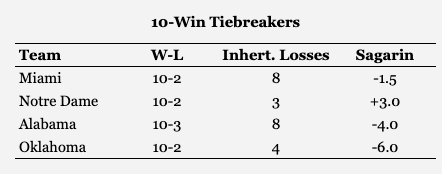

A naive way we can think about this is loss inheritance. Every time you lose to a team, instead of getting 1 loss, you inherit its losses. So Notre Dame lost to 1-loss Texas A&M and a 2-loss Miami, so it inherits 3 losses. Miami lost to 4-loss Louisville and 4-loss SMU, so it inherits 8 losses. 3 is fewer losses than 8, so Notre Dame is the better team.

We can use the same analysis to compare Vanderbilt (+2 from Alabama and +3 from Texas) and Alabama (+7 from Florida State and +1 from Georgia). Vanderbilt and Alabama both have 2 losses. Vanderbilt would be rated higher than Alabama in this case.

The flaw here is obvious: this is a second order analysis a bit detached from the actual results of the season. The statistician’s retort is that season performance itself is actual a second-order phenomenon, detached from the strength of any given team – but that argument is going to fall on deaf ears with most of the football-watching public.

What can work?

So, what can be done to fix this?

I think you have to take a bit from each group.

From the traditional view:

At large teams are admitted to the College Football Playoff based on record

From the giant playoff view:

Five conference champions get in automatically, selected by conference in order of number of teams in the top 25

From the statistical view:

When there are apparent ties, an objective statistical rating system is used (Elo, Sagarin, or even a simple loss-inheritance model.)

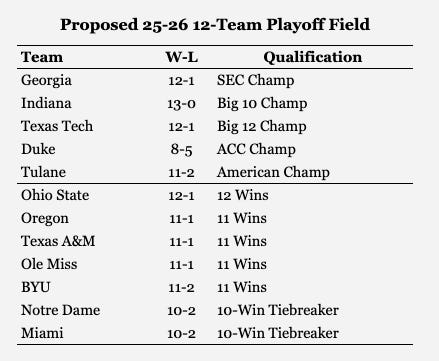

Using this approach, what would our 12-teams be in 2025-26?

With this approach:

Duke, BYU, and Notre Dame are in

Alabama, Oklahoma, and JMU are out

Duke takes JMU’s place, sneaking in as a conference champ.

BYU gets in because they’re an 11-win team. And Miami and Notre Dame beat Oklahoma and Alabama on statistical tiebreakers (assuming Sagarin rating system, which was used previously by the Bowl Championship Series.)