When you know, you know... or do you?

How many games does it take to know if what you're seeing is real. And what are we seeing at the top of the NBA this year?

Last month, we took a look at Wemby’s early season performance and… it looks like the one thing that was going to get in the way of Wemby has: Wemby has injured his calf and will be out for a few weeks.

Not a crisis – since the giant will ultimately be evaluated by his play in the post-season, but also – Wemby was already off track to have as good of a season as he needs to reach the performance levels we’re looking for.

Wembanyama was probably safely a top-10 player at the time of his injury. But wasn’t showing the consistent scoring necessary to crack top-5, let alone threaten Jokic, Doncic, or SGA for MVP votes.

What has been validated, though, is that with this version of Wemby, the Spurs are a really good team. And we can be confident about that even 13 games into the season.

But… small sample size?

The chorus of sample size is an argument that is often by levied by people who are either (a) cherry picking data or (b) don’t have a good empirical sense for what they’re talking about: they just don’t want you to be confident based on a handful of observations.

The truth of the matter is, small samples are powerful. Even a sample of 1 can help us ground a distribution.

If we’re watching a pitcher warm up, and we see him throw a 98 MPH fastball. We might not know much about his pitch velocity, but we’d be crazy to think he couldn’t hit 90 consistently in a game. We can use our general understanding of biology to get there – even if we know nothing about baseball.

The faster a pitcher throws a single pitch, the more confident we can be he throws fast. In the same vein, the better a team plays over a small sample of games, the more confident we can be that a team is actually good.

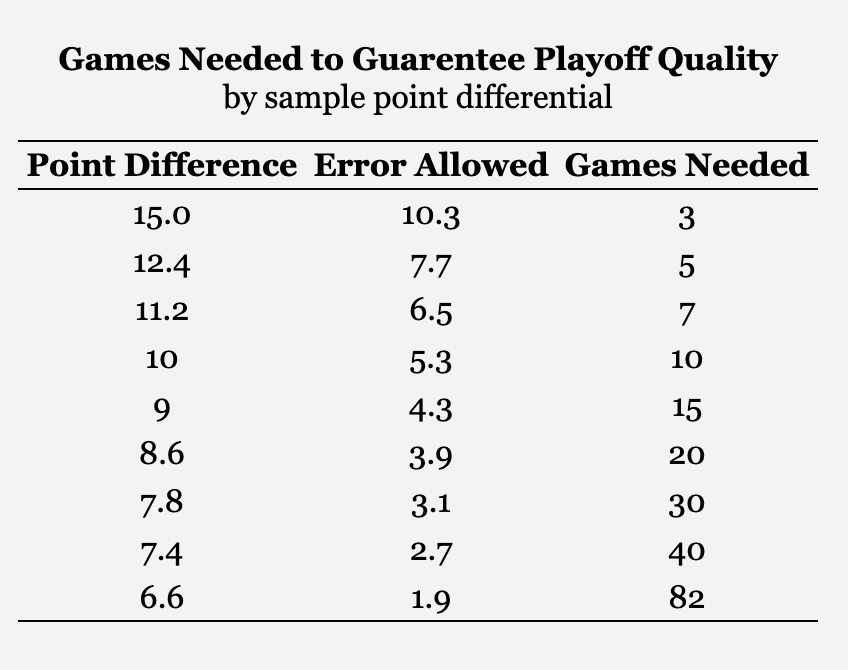

In the NBA, if a team averages a point differential of 15 points over just three games, we can be confident (+90%) that that team is going to be make the playoffs. As the average point difference for a team goes down, the number of games we need to be confident they’re going to make the playoff goes up.

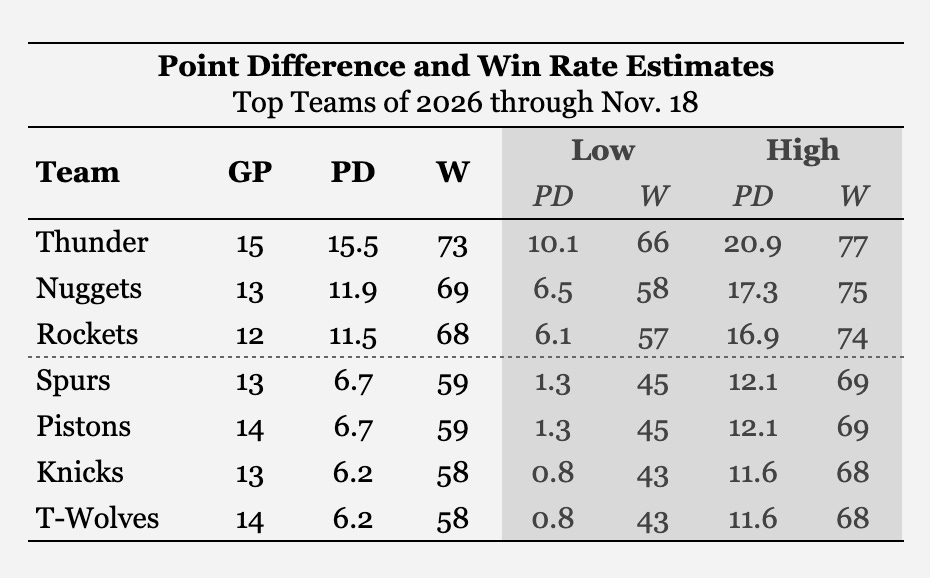

For example, the Thunder (+15.5), Nuggets (+11.9), and Rockets (+11.5) are all in after the opening month of games. We’ve seen what we need to see. These teams are good.

The rest of the teams – we won’t be able to tell until the season is over. Seriously. In most NBA seasons, the number of games played is simply not enough to delineate between medium-good teams. Great teams jump off the page. But medium-good teams? It’s hard to say.

The error rate of point differential after 82 games is +/- 1.9 points That means a team with a 5.0 point differential could be a 6.9 point differential team underperforming, a 3.1 point differential team over performing, or anywhere in between.

How good do teams need to be?

Lucky for all the teams we don’t yet know about – you don’t need to be a great team to win the NBA title. What you need to be is a good enough team with The Man on your team.

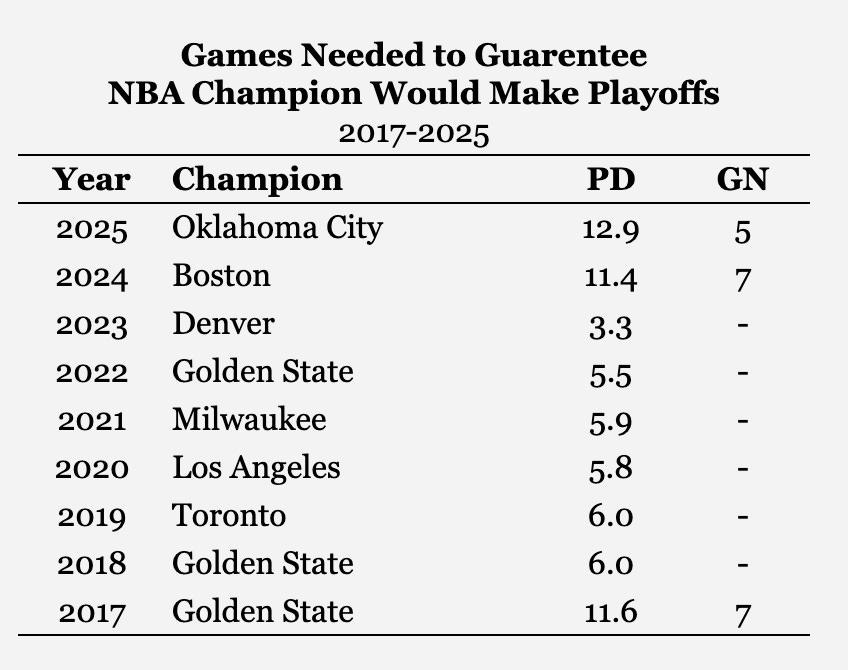

In recent history, only three teams have been good enough for us to confidently say – early in the season – that the teams are of playoff quality. This is one of the reasons we can’t really take total team quality into account when projecting performance within the playoffs: the error around team quality is bigger than the gaps.

Consider the NBA champions from 2017-2025. Only the ‘17 Warriors, ‘24 Celtics, and ‘25 Thunder passed the bar undisputedly good teams.

The others could just have plausibly been bad teams masquerading as good teams.

The worst team of the bunch, the ‘23 Nuggets, had a perfect storm of events: they had the reigning back-to-back MVP, a weak conference, and a complete collapse on the opposite side of the bracket. They faced the 7th seed Heat in the finals, who had a negative point differential on the season.

Crazy things happen. Call it small sample sizes.

What do we know about the best teams?

This year is looking special. At least at the top. The Thunder, Nuggets, and Rockets could all plausibly set the NBA single-season win record and it wouldn’t be that surprising. At least not based on how well they’ve been playing this far through the season.

The Rockets especially, who have a very team-centric style of play, are good candidates to charge through the season with a strong performance.

The reigning champion Thunder are harder to comment on, because being the champion places a bit less emphasis on the regular season. And the Nuggets are very reliant on a single player – so one injury could easily dash their record.

The table below shows estimated win rates for each of the top 7 teams, by point differential, as well as the lower and upper estimates of performance. That’s a 10th or 90th percentile mark where we’d be a bit surprised if something exceeded that range. Not terribly surprised, but pretty surprised.

One thing a close observer will notice is that teams like the Spurs, Pistons, Knicks and T-Wolves, are also all playing quite well. Compare the projections in this table to the table of NBA Champions above and you’ll find that many are currently playing at a level above what previous champions played at.

This is an odd year in that respect.

We should expect some of these teams – about half – to be playing worse by the end of the season. But if the Thunder, Nuggets, Spurs, and Knicks are all playing worse than they are now – that probably only takes two teams, the Spurs and Knicks, below a 6.0 point differential. Two thirds of the time in the last decade, a 6.0 point differential better than the reigning NBA champ.

We could plausibly have five teams playing above that level this year.

The last time we saw that was the 1998 season: when Michael Jordan won his final title, final MVP, and final scoring title over a crowded field that included a basketball team in Seattle.

That the last time we saw this many teams playing this well, the team with the league MVP won the title, should not come as a surprise. In fact, this should be out default assumption: the team with the reigning MVP, or that years MVP, will win the title.

The teams to watch out for from that angle? The current two best teams – Denver and Oklahoma City – and the lingering Lakers. The Luka and LeBron combination could be scary, if it finds a groove at the right time.

How does this apply to other sports?

The analysis here is empirical and numerical. That means real results from real basketball games are used to derive the distributions and outcomes – not statistical theories (although, the bootstrap, a technique used heavily here, can be considered a statistical theory in another sense).

Each sport is going to have different rates of information gain. Point differential in all sports, however, is a useful proxy for performance.

In baseball, there’s even a pretty well respected theory of run creation that can estimate true run differential and indicate the direction we’d expect run differential to correct to over time.

The base idea, though, that teams that are doing very, very well, are less likely to be a fluke than teams doing just kind of sort of well, is something you can carry across all sports.

The Avalanche are good in the NHL this year. The Capitals… open question.

Likewise, there’s reason to feel more confident about the Colts than the Eagles.

Whether you can feel confident about either of them… that’s an empirical question for another day.